The long way towards resilience - Part 8

Responding to changing threat landscapes

The long and winding road towards resilience - Part 8

In the previous post, we discussed what we find at the high-plateau of basic resilience.

In this post, we will discuss what is still missing to continue our journey to the top of Mt. Resilience. While discussing the missing ingredient, we will also broaden our view once more and find a familiar obstacle on our way.

Let us get started.

Standing still

As we have discussed in the previous post, we achieved resilience at the high-plateau of basic resilience, i.e., the ability to successfully cope with expected and unexpected adverse events and situations. We also saw we still lack the ability to evolve, to reposition ourselves in the face of a changing threats surface (with “threats” meaning adverse events and situations, see clarification in the next section).

This can be okay in relatively static or slowly evolving contexts that do not change too much over time. In such a setting we know quite well, how to handle the expected threats, and unexpected ones – the surprises – do not occur too often. If we are able to resist most surprises and to recover quickly from the few surprises that knock us over, everything is fine.

However, often environments tend to be highly dynamic, also regarding their threat surface. The nature of threats tends to change over time. Some threats that happened frequently in the past, tend to dry up. Others, that never occurred in the past start to happen more and more often. Interaction channels that were safe in the past become a major source of threats. And so on.

We might have everything at hand to respond to all kinds of expected and unexpected threats. Still, it might not be the most sensible response to a threat that happens more and more often to always get knocked over – even if we know how to stand up again quickly. Instead, we might want to figuratively step a bit aside, to reduce the impact of the blow, ideally making sure the adverse event or situation does not hit us anymore. 1

This idea of continuous learning and evolution leads us towards the peak.

The business side of threats

But before we continue our journey towards the peak of Mt. Resilience, we first need to broaden our view a bit and discuss what we actually talk about if we talk about availability and failures.

In the previous posts, we discussed a lot about availability. Especially, we talked a lot about failures, i.e., the loss of availability due to threats. I use the term “threat” here in accordance with the literature as a short form for any kind of adverse event and situation that needs to be handled, that poses a problem if unhandled – ranging from annoying to life-threatening.

I only introduce the term here because most people only think of IT-security-related adversities if they hear “threat”. This is why I explicitly wrote about “adverse events and situations” in the prior posts of this series – to make clear we are not only talking about IT security but about adversities in general.

However, the term “threat” is not (and never was) limited to security-related adversities but denotes any kind of adverse event or situation that leads to a problem if unhandled. As we advanced far enough in this blog series that you are able to avoid this widespread mental short-circuit, I think it is save to use the more widespread and less unwieldy term “threat” to denote adverse events and situations without automatically reducing it to IT security issues.

Having clarified the meaning of the term “threat”, what does it actually mean if a threat strikes, if a failure occurs, if a system becomes unavailable?

If we look at the bigger picture, we realize that availability and its sibling reliability are just indicators. Ultimately, we do not care about availability (or reliability). We care about the business level problems caused by the lack of availability (or reliability). If an IT system fails, it poses a business level threat, e.g.:

- People are stressed and unhappy

- Work cannot be done

- Machines cannot produce

- Accidents happen

- People are harmed, injured or even die

Depending on the actual impact of the system failure, this can have significant monetary, legal and reputational consequences, ranging from being annoying to an existential risk for the company. Thus, whenever we talk about an adverse events or situation (or threat), about failures triggered by them and about availability (or reliability), ultimately we talk about the business level risks activated by them.

The sameness of business and IT

We have already noticed a shift from a pure focus on technology to a stronger business-level focus over the course of the previous interim stops. At the peak of Mt. Resilience, our focus has completely shifted towards a business-level risk perspective. Of course, the IT systems still need to work in a highly dependable way to avoid unnecessary risks. However, they have become just one building block of a bigger picture that usually spans the whole company.

You might say: But we are just IT. We cannot change the whole company.

And probably you are right.

To be clear: As a software engineer, you do not need to change your whole company. It is enough if you care about creating, running and evolving dependable IT solutions because this already has a very high impact. Due to the ongoing digital transformation (I have written in more detail about this topic, e.g., in this post and this post), business and IT have become inseparable.

Besides other things, the ongoing digital transformation means these days business cannot be changed anymore without touching IT. You cannot launch a new business-level feature anymore without supporting it in your IT systems. You cannot change a business process anymore without changing it in your IT systems, too. And so on.

This means, among other things IT delimits how fast and flexible the business side can respond to new needs and demands from the market. IT especially delimits how fast a company can respond to a threat of any kind – be it a business threat or a technical threat. IT delimits how well you can eliminate or at least mitigate the unexpected risks, how resilient your company can become.

Of course, to become actually resilient, a company needs to do quite a bit more than just building a resilient IT. However, without a resilient IT a company cannot become actually resilient.

Thus, even if I write about topics here that seem to be far away from IT in the first place, due to the effects of the ongoing digital transformation, IT is always just a tiny step away. All those seemingly non-IT topics affect IT – and IT affects all those seemingly non-IT topics.

Therefore: It is fine if you limit your scope to IT while attempting to become more resilient. Just keep in mind that all your resilience efforts ultimately are part of a bigger picture and understand how your work affects the bigger picture and vice versa. This understanding is essential to ensure the effectiveness of your work and avoid working in vain. It also helps a lot when discussing the value of your work with non-IT people.

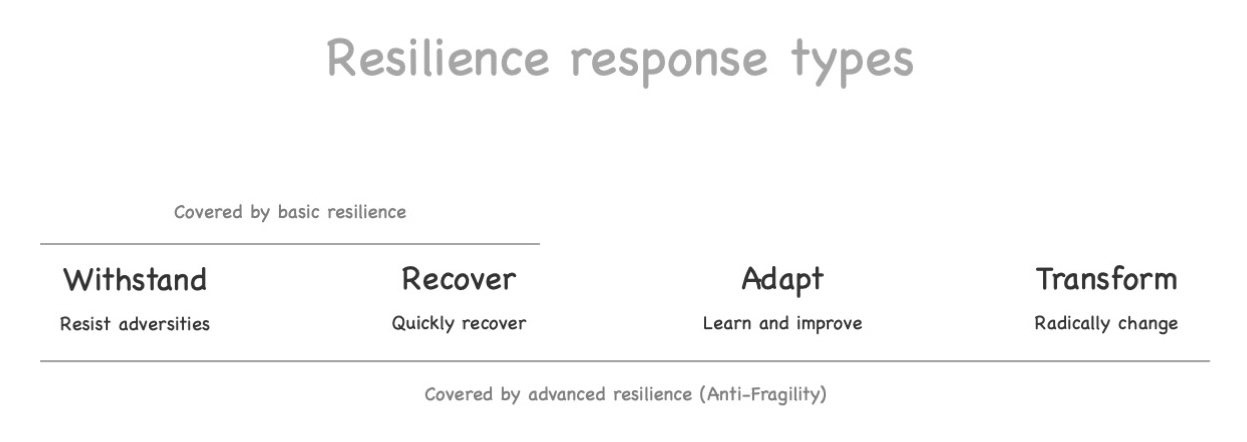

Resilience response types

After this digression outlining the bigger picture, we can continue our journey towards the peak of Mt. Resilience. We have seen that knowing how to respond to threats without evolving our threat response strategies is not necessarily sufficient. In many situations, it is important to respond to a continuously changing threat landscape and therefore also to continuously evolve our threat response strategies.

This brings us to the resilience response types. Resilience basically knows four different response types:

- Withstand – Having enough capacity and resources to resist the threat

- Recover – Being knocked over by the threat but having the ability to recover very quickly

- Adapt – Continuously adapting the threat responses to a changing threat surface

- Transform – Changing radically. Only applied if adaptation is not enough to remain in a viable area

If we transfer the resilience response types to a boxing match, it would translate like this (within the limitations of the analogy):

- Withstand equals a good defense: You make sure the blows do not get through and hit you.

- Recover equals building good taker qualities: Even if a blow gets through, you are able to recover from it quickly and continue the match. 2

- Adapt equals continuously changing your position and strategy in consideration of your opponent’s movements and attacks to make it harder for your opponent to land a blow and bring yourself in a more favorable position. While this seems to be obvious regarding a boxing match (most likely the match would end quickly with your knock-out if you would simply repeat the same motion the whole time), many companies apply such a static approach regarding threat response.

- Transform equals leaving the boxing ring and try a different kind of sports if you learn that your chances of succeeding in a boxing match are just too low.

Be aware that all analogies eventually break. Building a resilient IT is fundamentally different from boxing. Still, the analogy may be useful to grasp the ideas behind the response types better – especially to understand the difference between adapting and transforming.

The first two response types probably look familiar. They are the ones we find at the high-plateau of basic resilience. Either the threat is completely averted or a quick recovery from the impact takes place.

This also reminds the first two plateaus a bit (even though they are limited to known failure modes): The plateau of stability thinks in terms of withstanding while the plateau of robustness also includes mitigation and recovery, mitigation being sort of a middle ground between withstanding and recovery.

The last two response types add a new perspective: Instead of simply handling the threat in a sensible way, we might decide to change our positioning relative to the threat. These response types do not focus so much on the actual handling of the threats. Instead, they focus on changing the positioning to get out of the way of threats as much as possible. 3

This means in practice that we continuously analyze the threats, their frequency and their impact. Then we use the learnings to change our positioning, organization and collaboration modes to bring us in a better position where threats do not hit us as often anymore and/or their impact becomes less severe.

Adapting to the last two response types, we evolve from a mostly static threat response approach towards a dynamic one – where we constantly learn, move and evolve to optimize our positioning in a constantly changing threat landscape.

This also means, we need to embrace adversities instead of avoiding them in order to learn from them and to move to a more favorable position in the global threat landscape. This change of mindset reminds a bit of the movement from the plateau of stability towards the plateau of robustness. There we needed to change our mindset from avoiding failures to embracing failures. And as with that prior change of mindset, we can expect that this change of mindset towards embracing adversities most likely again will be the biggest obstacles on our way from the high-plateau of basic resilience to the peak of advanced resilience.

Anti-fragility

This changed response approach regarding adverse events and situations leads us to the peak of Mt. Resilience, the peak of advanced resilience – or anti-fragility.

You might remark now that Nicolas Taleb wrote in his book “Anti-fragility” that anti-fragility would be something essentially different than resilience. However, he used a definition of resilience that only included the first two of the aforementioned resilience response types. If you limit resilience to this rather static approach, Taleb would be right. But if you include all four response types as most resilience approaches do, resilience also covers anti-fragility. 4

Summing up

The resilience response types revealed the missing ingredient on our way to the peak of Mt. Resilience, the ability to continuously learn and adapt to an ever-changing threat landscape. This adds the last missing shard to resilience: Anti-Fragility.

On our way, we have also discussed the inseparability of business and IT. We have seen that due to the effects of the ongoing digital transformation everything you do to your IT also affects your business. We have seen that if we discuss IT system failures, we actually talk about business level threats, about people and organizations suffering from the impact of those threats.

Finally, we have realized that moving from the high-plateau of basic resilience to the peak of advanced resilience includes another mindset shift: From avoiding adversities to embracing adversities – which is probably the biggest obstacle on our way to the peak of Mt. Resilience.

In the next post, we will explore the peak of advanced resilience (anti-fragility). Stay tuned … ;)

-

Take, e.g., cybercrime as an example of a highly dynamic context where the threat surface changes continually. While some firewalls and an anti-virus software on your desktops were good enough in the past to handle cybercrime, they are certainly not good enough these days. Also, SIEM solutions that were considered state of the art for a while, are not sufficient anymore. In addition, anti-virus software on your desktops meanwhile have become as much part of the problem as they are part of the solution (because they run with highly elevated system privileges and thus have become preferred cybercrime targets). The fact that many companies still act very statically in such a highly dynamic environment makes them very vulnerable for cyberattacks. Thus, in a highly dynamic context where the threat surface continually changes, it is typically not sufficient to limit ourselves the kind of static resilience as we have seen it at the high-plateau of basic resilience. ↩︎

-

I am not sure if it is actually possible to build good taker qualities regarding a boxing match or if you simply have them or not. Maybe, this is a place where the analogy breaks. ↩︎

-

This reminds a bit of the highest tier a master can reach in some martial arts disciplines: The skill to influence and shape the environment in such a way that fighting is not needed anymore. ↩︎

-

My personal interpretation is that Mr. Taleb – as many people – sometimes tweaks definitions a bit to fit his train of reasoning better. I guess, we all do that sometimes. However, it also reminds us not to automatically assume something being correct just because some smart person said it … ;) ↩︎

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email